Godot: What's in a signature?

Why Care About Method Signatures?

I’ve been stuck in Godot’s “tutorial hell” for a while now. Every time I finish a 12-hour tutorial on building yet another detailed 3D platformer, I realize I still can’t apply anything I’ve learned. Others who’ve faced the same frustration on the Godot forums and subreddit are often told to just RTFM and build a game from scratch, avoiding tutorials as much as possible. After almost a year of dabbling with Godot every other weekend, I finally took that advice and started reading as much of the Godot documentation as I could.

While the Godot API reference is packed with useful methods for nearly every engine feature imaginable, I struggled to understand which methods applied where, and why some parameters were mandatory while others were optional. It wasn’t until I watched this video that I finally understood how the Godot APIs work—and I wish this had been the first thing I learned1.

1. Parameters: What’s Default and What’s Mandatory?

Every method in Godot has a parameter list, which specifies the inputs it needs to function. But how do you tell which parameters you must provide and which ones are optional? Let’s take a look at the PhysicsDirectSpaceState2Ds intersect_point method:

1

intersect_point(parameters: PhysicsPointQueryParameters2D, max_results: int = 32)

The above method is usually used to see if the point (the provided parameter) is inside of another solid shape. Here’s the breakdown:

parameters: PhysicsPointQueryParameters2D: This is required because there’s no default value assigned to it. If you don’t provide this argument, the function doesn’t know what to process, and Godot will throw an error.max_results: int = 32: Optional, because it has a default value (32). If you don’t specify this, Godot will use32automatically.

How to Spot Default Parameters:

- In the documentation, default (i.e.: optional) values are explicitly listed.

- If there’s no default value, the parameter is mandatory.

Always check the docs to see if parameters are optional—it can save you debugging time.

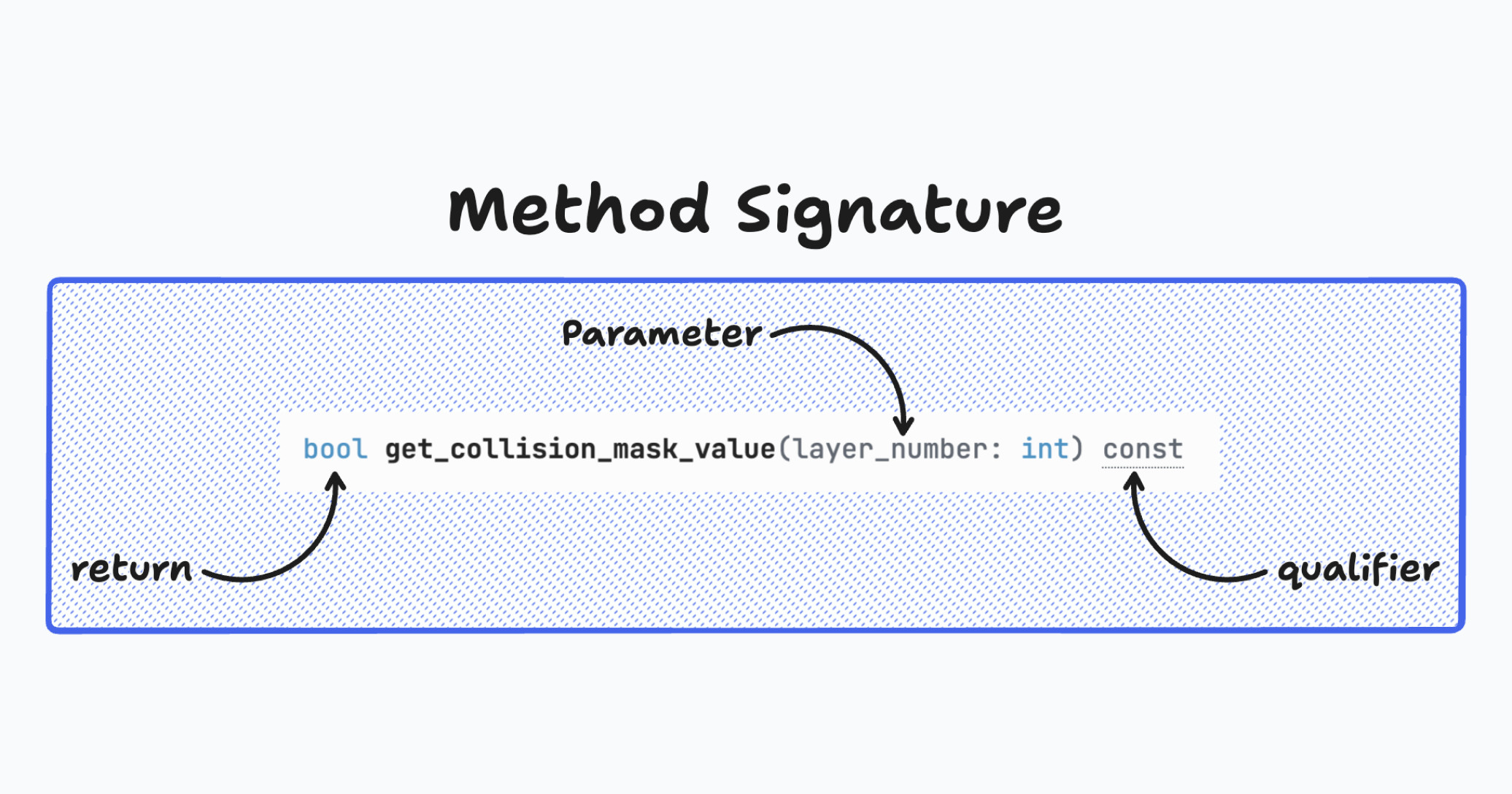

2. Qualifiers: What Do const, vararg, and Others Mean?

Qualifiers are like adjectives—they modify the behavior of the method. Here are some common ones you’ll encounter in Godot:

a. const

Indicates that the method doesn’t change the state of the object. Think of it as a “read-only” operation.

A good example of this is the get_global_mouse_position(), a method which simply returns the mouse’s position in the CanvasLayer that the relevant CanvasItem is in using the coordinate system of the CanvasLayer.

Why it matters: Methods marked as const are safe to call without worrying about side effects. It’s just like converting a value from metric to imperial, the value itself doesn’t change. Another popular method marked as const is rad_to_deg(), which converts an angle expressed in radians to degrees.

b. vararg

Short for “variable arguments.” This qualifier means the method can accept a variable number of arguments. You’ll usually see this in methods like print(), or rpc_id().

Example:

1

print("Hello", "World", 42)

Internally, vararg lets Godot handle the extra arguments dynamically.

If you look at the documentation for the rpc_id method, you’ll see this:

1

rpc_id(peer_id: int, ...) # vararg const

The ... indicates that after specifying the peer_id, you can provide additional arguments for the remote function being called.

For example, let’s say you’re working in a multiplayer project and want to send dynamic data to specific peers:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

var player_info = {"name": "Name", "score": 100}

# When a peer connects, send them my player info.

# This allows transfer of all desired data for each player (i.e.: the player_info dictionary), not just the unique ID.

func _on_player_connected(id):

_register_player.rpc_id(id, player_info)

@rpc

func _register_player(info):

print("Player connected with info:", info)

Because the qualifier for this method is vararg, the method dynamically adapts to the arguments you pass. In the example, rpc_id sends a dictionary (player_info) as part of the remote call.

c. virtual

This means the method can be overridden by a derived class. Think of it as a template method that subclasses can modify.

The most famous examples would be _on_ready() and _process(). These functions are actually virtual methods of the Node class, which you override in almost every script you use when you extend anything that inherits Node. Example:

1

2

func _process(delta: float) -> void:

print("Anything you print here overrides the default built-in virtual method)

d. static

A static method belongs to the class itself, not to an instance. You can call it without creating an object. Let’s take Vector2.ZERO for example:

Example:

1

print(Vector2.ZERO) # Outputs: (0, 0)

In the above code snippit, you can directly access the ZERO property from the Vector2 class without creating an instance of Vector2. In other words, you don’t need to write:

1

2

var vec = Vector2()

print(vec.ZERO) # This is not valid; ZERO belongs to the class.

3. Return Types: What’s Coming Back?

Return types in a method signature tell you what kind of value to expect from the method. For example:

1

position.distance_to(other: Vector2) -> float:

- The

-> floatpart means this method will return a number (specifically, afloat). - If the return type is

void, the method doesn’t return anything.

Why Return Types Matter:

- They tell you what you can do with the result.

- For example, if a method returns a

Vector2, you know you can callnormalized()on it or use it in arithmetic.

1

2

3

var target = Vector2(10, 10)

var distance = position.distance_to(target) # distance is a float

print(distance)

-

While this sounds like frustration, it really isn’t. I’m not a developer by trade or training, just someone who enjoys exploring computers and the Godot engine in my free time. My goal isn’t to create a profitable game or to min-max my way through Godot and coding best practices as quickly as possible. I’m content with learning slowly, through trial and error, and appreciating details others might overlook—like how Godot uses bitmasks to identify layers in the code editor. ↩︎